Blog Archives

18. High School Balls: Early football at British public schools

We like the tales of the medieval horde wreaking havoc in the streets. We don’t even mind if they were Scottish medieval hordes. But the idea that football as we know it was the result of the refinery of the game by the privileged few at the poshest schools in England is one a lot of people would rather disprove than prove.

British schools clearly played an important part in the development of football, and elitist though they were, the public schools deserve particular credit. There are records of ball games being played from the 16th century, and the first specific reference to football was at Winchester in the 1640s, where it was described as “innocent and lawful.” Indeed, although there are cases such as Shrewsbury headmaster Samuel Butler famously saying it was “more fit for farm boys and labourers than young gentlemen,” there is little evidence of schools being especially opposed to their pupils playing football. And by the time Butler’s successor Benjamin Kennedy was in charge, not only was football tolerated at Shrewsbury, but pupils were forced to play it three times a week whether they liked it or not, and most other headmasters of the era shared the same enthusiasm.

British schools clearly played an important part in the development of football, and elitist though they were, the public schools deserve particular credit. There are records of ball games being played from the 16th century, and the first specific reference to football was at Winchester in the 1640s, where it was described as “innocent and lawful.” Indeed, although there are cases such as Shrewsbury headmaster Samuel Butler famously saying it was “more fit for farm boys and labourers than young gentlemen,” there is little evidence of schools being especially opposed to their pupils playing football. And by the time Butler’s successor Benjamin Kennedy was in charge, not only was football tolerated at Shrewsbury, but pupils were forced to play it three times a week whether they liked it or not, and most other headmasters of the era shared the same enthusiasm.

Discipline was a huge problem at these schools and no matter how brutal the corporal punishment, bullying and general disorder were common. Older pupils would use the younger ones as their ‘fags’, basically slaves, and one of the biggest concerns of all was what Uppingham’s Edward Thring called “the worm-life of foul earthly desires,” i.e. masturbation. As a doctor wrote in 1835, “a daily proper portion of bodily fatigue is the antidote to all wandering of the thoughts and dwelling on improper objects.” The Victorian era witnessed a boom in what was called Muscular Christianity, and the idea of ‘mens sana in corpore sano’ (a healthy mind in a healthy body). Football fit the bill perfectly.

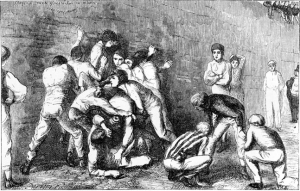

But unlike the regulated game of cricket, there was no standard set of rules. Each school went it alone, devising its own based on whatever balls, field and goalposts they had, allowing different levels of violence, with the ball sometimes only kicked and sometimes handled too. ‘Hacking’, the noble art of kicking your opponent in the shins, was a prominent element of football at most 19th century public schools, and most descriptions are so brutal that it’s hard to accept the common theory that the wealthier classes took the plebeian tradition of ‘mob football’ and made it into something more civilised.

But unlike the regulated game of cricket, there was no standard set of rules. Each school went it alone, devising its own based on whatever balls, field and goalposts they had, allowing different levels of violence, with the ball sometimes only kicked and sometimes handled too. ‘Hacking’, the noble art of kicking your opponent in the shins, was a prominent element of football at most 19th century public schools, and most descriptions are so brutal that it’s hard to accept the common theory that the wealthier classes took the plebeian tradition of ‘mob football’ and made it into something more civilised.

As these games were only ever played among isolated and tightly-knit school communities, all kinds of local peculiarities would be added, to the extent that most of them became so excruciatingly complicated that most outsiders struggled to understand what was going on. It was said of Eton’s game in 1832 that “the interminable multiplicity of rules about sneaking, picking up, throwing, rolling in straight … would probably be to many readers as perfect Hebrew as they are to us.” This was referring to the famous Wall Game, played along a wall built in 1717 in which two closely knit packs of bodies called ‘bullies’ battle to get the ball into the ‘calx’ zones at either end. The game is still played at Eton today, as is its sister-sport, the  Eton Field Game, best described as rugby played with the feet and using soccer goals, but with a host of added complexities concerning such matters as ‘furking’ (heeling the ball backwards in the ‘bully’), touching balls down behind the goal-line to score a ‘rouge’, ‘sneaking’ (offside) and the brutal conversion attempts in which three players bind together to form a kind of battering ram. Many of the Field Game’s rules seem in some way or other to have been imported from the Wall Game, and a glance at the first recorded set of rules, from 1847, shows how much it has changed. Originally it was much simpler, and strikingly similar to the game the Football Association would endorse in 1863, including the same offside rule and the way that a free kick was awarded to anyone caught the ball on the fly.

Eton Field Game, best described as rugby played with the feet and using soccer goals, but with a host of added complexities concerning such matters as ‘furking’ (heeling the ball backwards in the ‘bully’), touching balls down behind the goal-line to score a ‘rouge’, ‘sneaking’ (offside) and the brutal conversion attempts in which three players bind together to form a kind of battering ram. Many of the Field Game’s rules seem in some way or other to have been imported from the Wall Game, and a glance at the first recorded set of rules, from 1847, shows how much it has changed. Originally it was much simpler, and strikingly similar to the game the Football Association would endorse in 1863, including the same offside rule and the way that a free kick was awarded to anyone caught the ball on the fly.

Harrow also still plays its traditional form of football, which particularly took off after sports enthusiast Dr Charles John Vaughan became headmaster in 1844. It’s played on an often very muddy field into goals called ‘bases’ that, as in Aussie Rules, have no crossbar, and using a heavy and awkward ‘porkpie’ shaped ball. Like in rugby, the ball cannot be passed forward, and American football-like interference is also legal, while as in Aussie rules, if a kicked ball is caught in the air, a player wins a free kick called ‘yards’.

Another game that has survived into the 21st century is what Winchester College calls Winkies. As complex as Eton’s game, it was said in 1936 that “it would take a parliamentary council to draft it intelligibly,” with the general idea simply being to kick the ball into the end-zone, called ‘worms’, but such added peculiarities as the teams taking turns to kick the ball, play restarting with a scrum called a ‘hot’ and a form of bonus scoring called a ‘behind’, which quite probably inspired the use of the same word for something similar in Australia. On either side of the pitch are what are called ‘canvasses’, nets erected to keep the ball from leaving the field, but also held up by posts which are used to divide the ground into different zones, which come into play at certain points.

Another game that has survived into the 21st century is what Winchester College calls Winkies. As complex as Eton’s game, it was said in 1936 that “it would take a parliamentary council to draft it intelligibly,” with the general idea simply being to kick the ball into the end-zone, called ‘worms’, but such added peculiarities as the teams taking turns to kick the ball, play restarting with a scrum called a ‘hot’ and a form of bonus scoring called a ‘behind’, which quite probably inspired the use of the same word for something similar in Australia. On either side of the pitch are what are called ‘canvasses’, nets erected to keep the ball from leaving the field, but also held up by posts which are used to divide the ground into different zones, which come into play at certain points.

Most other major schools once played their own games too. As early as 1611, it was written at Charterhouse about “boys all striving who should kick most wind out of the bladder.” In 1895, two Old Carthusians recalled how in their younger days players would gather in the ‘cloisters’ for a violent, shoving game in which “the ball very soon got into one of the buttresses, when a terrific squash would be the result, some fifty or sixty boys huddled together, vigorously rouging.”

Like most public school games, Westminster’s constantly changed its traditions over the years. Running with the ball, rugby-style, was once legal, and one old boy remembered that “when running … the enemy tripped, shinned, charged with the shoulder, got down and sat upon you – in fact did anything short of murder to get the ball from you. I think that this running and fist-punting was stopped in 1851 or 1852.”

In the 1840s, Marlborough College had its local complexities too, including ‘crewing’, ‘wheeling’ and ‘roking’. “Piles of coats supplied the first goal-posts … The rules, such as they were, and there were none in particular, were somewhat similar to those of the present Association game.” That changed when headmaster Charles Cotton arrived in 1852, when “rugby goalposts were erected and the rugby rules … practically adopted.” But in typical fashion, Marlborough adapted the rules as it pleased, introducing such elements as the ‘squash’, the ‘grovel’ and a ‘rouge’, which was basically the same thing as an American safety.

Rossall, Cheltenham, Haileybury, Uppingham, Radley … they and others all had their football games, but there was little or no tradition of schools playing each other as they did at cricket. “No one ever hears of two great schools contending on neutral ground in a game of football, no matter on how friendly terms they may subsist” it was said in 1868. Much of this was due to fear of the trouble it might cause. “The feud between Eton and Harrow is sufficiently well known to make an increase of hostile feeling very undesirable” said an Old Etonian in 1863, and one attempt at an inter-school match between Marlborough and Clifton in 1864 was such a hot-blooded affair that it was enough to convince several schools that football matches were a very bad idea.

Rossall, Cheltenham, Haileybury, Uppingham, Radley … they and others all had their football games, but there was little or no tradition of schools playing each other as they did at cricket. “No one ever hears of two great schools contending on neutral ground in a game of football, no matter on how friendly terms they may subsist” it was said in 1868. Much of this was due to fear of the trouble it might cause. “The feud between Eton and Harrow is sufficiently well known to make an increase of hostile feeling very undesirable” said an Old Etonian in 1863, and one attempt at an inter-school match between Marlborough and Clifton in 1864 was such a hot-blooded affair that it was enough to convince several schools that football matches were a very bad idea.

But there was also the major inconvenience of the total lack of any established set of rules, and with such snobbery between the rival institutions, there was very little interest in making compromises. Tellingly, Charterhouse was the only school to accept the invitation to the first meeting of the FA in 1863, and it was mainly because of such disinterest that the FA’s new game struggled to gain acceptance in its formative years.

But unified football got there in the end, and the old schools games eventually all suffered the same fate as that of Stonyhurst, where it was lamented in 1904 that “Stonyhurst football is now, alas! being superseded by the more up-to-date Association Rules and the grand matches … are a thing of the past.”

That is, apart from Eton, Harrow and Winchester, who still play their games today. And although many critics would second the idea that these surviving games are “ritual offerings to  an unknown god” that merely “colour the image of these schools’ peculiar and traditional nature” this seems to form part of something of a socialist backlash against them and their role in the formation of modern-day football, with football historians often preferring, without too much reason, to hand the credit instead to the working classes and their Shrovetide games. Most elements of the modern football codes can be traced in some form or other to public school traditions, and many graduates of these schools were involved in the early rules-making.

an unknown god” that merely “colour the image of these schools’ peculiar and traditional nature” this seems to form part of something of a socialist backlash against them and their role in the formation of modern-day football, with football historians often preferring, without too much reason, to hand the credit instead to the working classes and their Shrovetide games. Most elements of the modern football codes can be traced in some form or other to public school traditions, and many graduates of these schools were involved in the early rules-making.

Shrewsbury’s game called ‘douling’ is particularly important in that respect. Its rules were practically identical to those drafted at Cambridge University in 1848, at a meeting called by two Old Salopians called Henry de Winton and John Charles Thring, and the earliest surviving copy of those rules was found in the Shrewsbury library. It was said that “between 1854 and 1860 there were few better players at Cambridge than Shrewsbury men,” and it was those very rules that were used as the basis for those decided at the first sessions of the Football Association in 1863.

Of course, one other game played at a public school would have a huge bearing on the future of football around the world. And that school is, of course, Rugby…

Click here to buy the book and read the whole story.

19. ALL ELLIS BREAKING LOOSE: Rugby School and the origins of rugby