14. Bandy on the run: More on the origins of the hockey codes

One of the strongest campaigners for the right to be known as the birthplace of ice hockey is Windsor in Nova Scotia, where it is argued the surname Hockey is a common one, and even that a certain Colonel Hockey was one of its creators. It’s absolute hockey-cock, because as we learned earlier, the Galway Statutes in Ireland made reference to ‘hockie stickes’ as far back as 1527.

From Chinese ‘guoguipo’ and aboriginal Australian ‘dumbing’, to Chilean ‘palin’ and Russian ‘kotol’, team games in which a ball was struck with a stick were by no means unique to the Celts. An image on a second century mould found in Northamptonshire and medieval stained glass images in Canterbury and Gloucester cathedrals suggest that England had a stickball tradition too. Names like ‘comocke’, ‘shinnup’ and ‘hurl-bat’ suggest an obvious link with the Celtic games, while other names included ‘bandy’, ‘scrush’, ‘jowling’ and ‘crabsowl’.

From Chinese ‘guoguipo’ and aboriginal Australian ‘dumbing’, to Chilean ‘palin’ and Russian ‘kotol’, team games in which a ball was struck with a stick were by no means unique to the Celts. An image on a second century mould found in Northamptonshire and medieval stained glass images in Canterbury and Gloucester cathedrals suggest that England had a stickball tradition too. Names like ‘comocke’, ‘shinnup’ and ‘hurl-bat’ suggest an obvious link with the Celtic games, while other names included ‘bandy’, ‘scrush’, ‘jowling’ and ‘crabsowl’.

Oddly, despite the Galway Statutes mentioning “hockie sticks” way back in 1527, there is no record of the word being used again until “a game at hockey” is described in an 1822 children’s book. It is therefore curious that the term hockey’ would come to replace most of the older names.

The 1822 reference states that hockey “is not a game that is now in general use,” apparently because schools had banned it due to the dangers. Eton in 1832 reckoned it was “the only place in England where this ancient custom is kept up” and although this wasn’t strictly true, for the next half-century or so, whenever hockey is mentioned, it is almost always described as sport that was going out of fashion along with shinty and hurling, which most observers felt to be the same game under a different name.

The 1822 reference states that hockey “is not a game that is now in general use,” apparently because schools had banned it due to the dangers. Eton in 1832 reckoned it was “the only place in England where this ancient custom is kept up” and although this wasn’t strictly true, for the next half-century or so, whenever hockey is mentioned, it is almost always described as sport that was going out of fashion along with shinty and hurling, which most observers felt to be the same game under a different name.

Two London clubs were largely to thank for maintaining the tradition. Blackheath was claimed to be formed as early as 1840 and played a violently physical version with a cube-shaped ball, while Teddington wrote the Surbiton Rules in 1874, which banned all use of the hands and feet and also the striking of the ball in the air. They founded the Hockey Association in 1886, but struggled to attract followers in a world where football was now the national obsession. Blackheath (the same club that had argued rugby’s case against soccer when the FA was formed in 1863) established an unsuccessful rival association to govern their more physical game, the Scots were unimpressed by “an innocent, innocuous apology for camanachd” and although hockey was particularly successful in Ireland, Michael Cusack would soon be forming the GAA and advocating a return to a more physical game in the guise of ‘hurling’.

These were the final years of the ‘Little Ice Age’, meaning the idea of hockey played on ice was still very feasible in Britain. Sir John Dugdale Astley’s memoirs speak of “an on-ice version of field hockey” that he’d even played before Queen Victoria in 1853. It was especially popular in the East English Fenland, where it was known as ‘bandy’, and particularly thanks to the efforts of Charles Tebbutt, the national association founded in 1891 started promoting the game abroad, finding natural allies in Holland, where there was an old tradition of similar games. By 1913, there were enough countries involved for a European Championship to be held. But the First World War ended almost all interest in the game, except in Scandinavia, where this combination of ice hockey and football is still popular today, and also in the Soviet Union, where there was such a strong tradition of similar games that composite rules were written in 1955 for the benefit of international play.

These were the final years of the ‘Little Ice Age’, meaning the idea of hockey played on ice was still very feasible in Britain. Sir John Dugdale Astley’s memoirs speak of “an on-ice version of field hockey” that he’d even played before Queen Victoria in 1853. It was especially popular in the East English Fenland, where it was known as ‘bandy’, and particularly thanks to the efforts of Charles Tebbutt, the national association founded in 1891 started promoting the game abroad, finding natural allies in Holland, where there was an old tradition of similar games. By 1913, there were enough countries involved for a European Championship to be held. But the First World War ended almost all interest in the game, except in Scandinavia, where this combination of ice hockey and football is still popular today, and also in the Soviet Union, where there was such a strong tradition of similar games that composite rules were written in 1955 for the benefit of international play.

Canada is said to be the home of ice hockey, but although the modern laws were written in Montreal in the 1870s, these were the same as the rules for English field hockey, other than one modification to include the word ‘ice’. The claim that ice hockey was an entirely Canadian invention is questionable. The only truly Canadian innovation would seem to be the puck, introduced in 1875 for the safety of the spectators.

Canada is said to be the home of ice hockey, but although the modern laws were written in Montreal in the 1870s, these were the same as the rules for English field hockey, other than one modification to include the word ‘ice’. The claim that ice hockey was an entirely Canadian invention is questionable. The only truly Canadian innovation would seem to be the puck, introduced in 1875 for the safety of the spectators.

The Canadian climate was obviously well-suited to the sport, so it was a logical place for it to boom. Among several examples, a poem written in Dartmouth in 1823 describes how “now at ricket with hurlies some dozens of boys chase the ball o’er ice with a deafening noise”, in 1829 the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia refused to heed to public pressure to outlaw “hurly on the ice”, and in 1844 a quote from a Thomas Haliburton novel speaks of “hurly on the long pond.” Some argue whether these were really references to ice hockey in the truest sense, but there is no doubt about an article titled Winter Sports in Nova Scotia that describes an 1859 game in which teams of skaters battled with hurlies to score through what was called a ‘ricket’.

However, William Alexander Fuer’s comment of 1783 that “the icy surface was alive with skaters … bearing down in a body in pursuit of the ball driven before them with their hurlies” is older than any of these, but refers to a game not in Canada, but in New York. Even in a preview of the game in Montreal in 1875 that is said to have started modern ice hockey, it is tellingly stated that the sport although “much in vogue on the ice in New England and other parts of the United States, is not much known here.”

However, William Alexander Fuer’s comment of 1783 that “the icy surface was alive with skaters … bearing down in a body in pursuit of the ball driven before them with their hurlies” is older than any of these, but refers to a game not in Canada, but in New York. Even in a preview of the game in Montreal in 1875 that is said to have started modern ice hockey, it is tellingly stated that the sport although “much in vogue on the ice in New England and other parts of the United States, is not much known here.”

Ice hockey grew out of a number of different traditions on both sides of the Atlantic and both sides of the 49th parallel, and it is clearly pointless for any one place to claim to have been its birthplace.

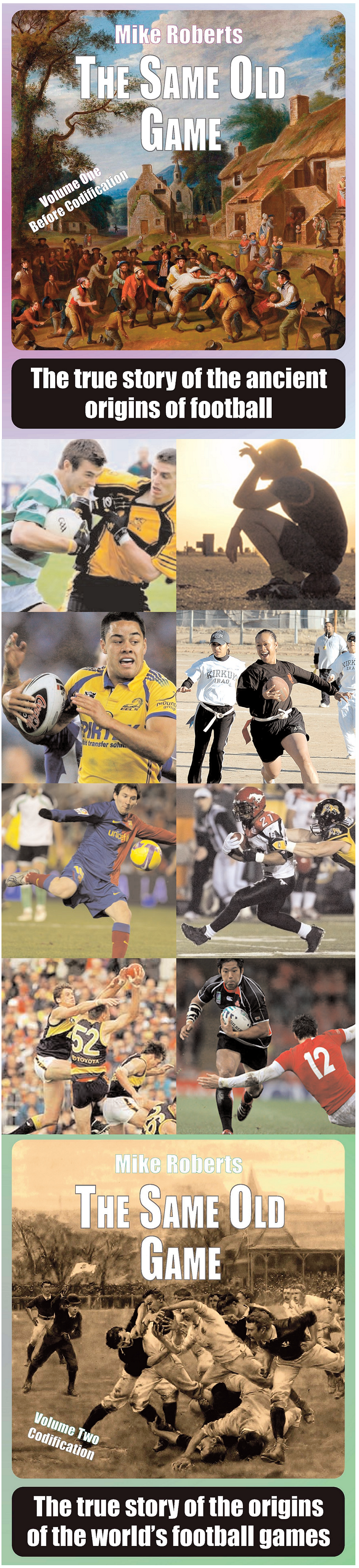

Click here to buy the book and read the whole story.

Leave a comment

Comments 0