19. All Ellis Breaking Lose: Rugby School and the origins of rugby

May he long rest in peace. It’s a nice story, and we all need something to believe in. And if that belief is in a man called William Webb Ellis, then no harm is done to anybody.

In the Warwickshire town of Rugby, “crying no football play in ye street” was mentioned in the local constable’s books five years before the local school purchased its playing fields in 1748 “for the recreation of the youth.” More than half a century would pass before football apparently became an important matter to the boys, but this would be the place where the most famous public school football game of all was born – Rugby football, and by extension, American football too.

In the Warwickshire town of Rugby, “crying no football play in ye street” was mentioned in the local constable’s books five years before the local school purchased its playing fields in 1748 “for the recreation of the youth.” More than half a century would pass before football apparently became an important matter to the boys, but this would be the place where the most famous public school football game of all was born – Rugby football, and by extension, American football too.

Matthew Holbeche Bloxham played it from 1813 onwards and described it extensively in a letter written nearly seventy years later, in 1880. Unlike most public school games, where it was played by limited teams, at Rugby the whole school was expected to turn out to play all at the same time, with well upward of a hundred players on each side. They were laid out like small armies, with the junior ‘fags’ forming a defensive mass on each of the goal-lines, while the seniors took centre stage. “Few and simple were the rules of the game … no one was allowed to run with the ball in his grasp towards the opposite goal. It was football and not handball, plenty of hacking, but little struggling” wrote Bloxham.

However, he then goes on to say that “in the latter half of 1823 … a boy of the name of Ellis, William Webb Ellis … caught the ball in his arms.” By the rules in force at the time in Rugby, and in most public schools, that won him the right to a free kick. However, “Ellis, for the first time, disregarded this rule, and … rushed forwards with the ball in his hands.” In 1895, the Old Rugbeian Society decided to research the claim (made by a man who had left the school three years before Ellis even arrived) by interviewing the few men alive that were old enough to remember. They gathered enough evidence to show that although Rugby football once resembled soccer “at some date between 1820 and 1830 the innovation was introduced of running with the ball [which was] of doubtful legality for some time … but obtained customary status between 1830 and 1840 and was duly legalised.” The society also accepted that Ellis had “in all probability” been the innovator, despite none of the interviewees ever having heard Bloxham’s story before, although one did remember that Ellis “was generally regarded as inclined to take unfair advantages at football.”

However, he then goes on to say that “in the latter half of 1823 … a boy of the name of Ellis, William Webb Ellis … caught the ball in his arms.” By the rules in force at the time in Rugby, and in most public schools, that won him the right to a free kick. However, “Ellis, for the first time, disregarded this rule, and … rushed forwards with the ball in his hands.” In 1895, the Old Rugbeian Society decided to research the claim (made by a man who had left the school three years before Ellis even arrived) by interviewing the few men alive that were old enough to remember. They gathered enough evidence to show that although Rugby football once resembled soccer “at some date between 1820 and 1830 the innovation was introduced of running with the ball [which was] of doubtful legality for some time … but obtained customary status between 1830 and 1840 and was duly legalised.” The society also accepted that Ellis had “in all probability” been the innovator, despite none of the interviewees ever having heard Bloxham’s story before, although one did remember that Ellis “was generally regarded as inclined to take unfair advantages at football.”

In 1987, the first Rugby World Cup was contested for the Webb Ellis Trophy, but it’s doubtful whether the man, who died in Menton in southern France in 1872, really had anything to do with the origins of the game at all. In any case, scrums, mauls, lineouts, the oval ball, tries and conversions, the absence of forward passing, the H-shaped posts and all of rugby’s other defining features had nothing to do with Webb Ellis, so it was probably nonsensical to celebrate 1923 as the sport’s centenary year.

In 1987, the first Rugby World Cup was contested for the Webb Ellis Trophy, but it’s doubtful whether the man, who died in Menton in southern France in 1872, really had anything to do with the origins of the game at all. In any case, scrums, mauls, lineouts, the oval ball, tries and conversions, the absence of forward passing, the H-shaped posts and all of rugby’s other defining features had nothing to do with Webb Ellis, so it was probably nonsensical to celebrate 1923 as the sport’s centenary year.

Thomas Hughes told the society that “in my first year, 1834, running with a ball to get a try by touching down within goal was not absolutely forbidden, but a jury of Rugby boys that day would almost certainly have found a verdict of justifiable homicide if a boy had been killed running in … the question remained debatable when I was captain of Bigside in 1841-42 when we settled it … running in was made lawful with these limitations, that the ball must be caught on the bound, that the catcher was not ‘off his side’, that there should be no ‘handing on’ but that the catcher must carry the ball and ‘touch down’ himself.” Picking up the ball from the ground was still illegal, as was throwing the ball to another player.

Hughes was the same man who, in 1857, published Tom Brown’s Schooldays, a bestseller that dedicated a whole chapter to football at Rugby and gives a very clear portrayal of what it was once like. In Hughes’ day, as forward passing was illegal, it was mainly one continuous ‘scrummage’ involving two huge packs of players battling to somehow kick the ball through the mass of bodies in front of them, with shins being kicked far more often than the ball. Players called ‘dodgers’ were positioned around the outside, “who seize on the ball the moment it rolls out from amongst the chargers and away with it to the opposite goal.” But only if caught on the bound could they actually carry the ball, a very difficult thing to do, and if the ball ever went out of bounds, “whoever first touches it has to knock it straight out amongst the players-up.” Hence the origin of the lineout, and also the term ‘touch’.

Hughes was the same man who, in 1857, published Tom Brown’s Schooldays, a bestseller that dedicated a whole chapter to football at Rugby and gives a very clear portrayal of what it was once like. In Hughes’ day, as forward passing was illegal, it was mainly one continuous ‘scrummage’ involving two huge packs of players battling to somehow kick the ball through the mass of bodies in front of them, with shins being kicked far more often than the ball. Players called ‘dodgers’ were positioned around the outside, “who seize on the ball the moment it rolls out from amongst the chargers and away with it to the opposite goal.” But only if caught on the bound could they actually carry the ball, a very difficult thing to do, and if the ball ever went out of bounds, “whoever first touches it has to knock it straight out amongst the players-up.” Hence the origin of the lineout, and also the term ‘touch’.

The H-shaped posts were already in place, and we are told the ball “must go over the crossbar, any height’ll do, so long as it’s between the posts.” This was the only way of scoring in those days, and not at all easy to achieve, but there was also the option of trying to defy the crowds of fags by crossing the goal-line and touching the ball down. This wasn’t considered a goal, but did earn your team the right to a ‘try at goal’ (and hence the origin of the term ‘try’), whereby the ball was kicked back into play and had to be caught by a team-mate before the rush of fags got to it first. If cleanly caught, the player marked the spot with his heel and from there an attempt was made to kick the ball over the crossbar. All this ceremony survived in rugby until the 1880s (and to a certain extent is still present in American football), while it was in 1886 that for the first time a point was awarded for obtaining a ‘try’ regardless of whether it was successfully converted.

The headmaster of Rugby from 1828 to 1841 was Thomas Arnold, a revolutionary educator who made Rugby one of the most respected schools in the land. But his role in the origins of its football has probably been overstated. Although “Rugby football had a great game in my day, and Arnold encouraged us to play it,” as Alexander Arbuthnot wrote in 1910, it would have been unthinkable for a master to have cared much about the rules. The game was entirely the doing of the pupils, and although Arnold wrote extensively on education, he never once expressed much of an opinion about the role sports could play in it.

The headmaster of Rugby from 1828 to 1841 was Thomas Arnold, a revolutionary educator who made Rugby one of the most respected schools in the land. But his role in the origins of its football has probably been overstated. Although “Rugby football had a great game in my day, and Arnold encouraged us to play it,” as Alexander Arbuthnot wrote in 1910, it would have been unthinkable for a master to have cared much about the rules. The game was entirely the doing of the pupils, and although Arnold wrote extensively on education, he never once expressed much of an opinion about the role sports could play in it.

Arnold’s death in 1842 led to an outpouring of emotions regarding his achievements and a desire to document everything about the school, which is probably why in 1845, three pupils, including his son William Delafield Arnold, were charged with writing the Laws of Football as Played at Rugby School. Rather than a complete list of Laws, “which are too well known to render any explanation necessary to Rugbeians,” these really only cleared up some of the finer issues, and references to what happened when the ball went near the trees and such instructions as ‘the Island is all in goal’ clearly show that they were only for local use. One major issue was the forging of sick-notes to get out of having to play, and “only in cases of extreme emergency … shall anyone be permitted to leave the close … till the game be finished.”

I n 1863, a writer in The Field asked “was the oval ball an accident from want of skill in the worker in leather in Rugby, who like the tailors then persuaded his victims that it was the true artistic shape?” The origin of rugby’s ‘outgrown egg’ is uncertain, for although it is said to have been the creation of a local shoemaker named Richard Lindon in 1862, that wouldn’t explain why Thomas Hughes had written in 1857 that the ball was “pointing towards the School or island goal.” Spherical balls can’t point. But even if HJ Lindon’s son was correct in advertising himself as the son of the “inventor of the true rugby ball and also inflator for the same,” the family foolishly failed to patent the idea. Instead it was their rival and Lindon’s possible former employer, William Gilbert, who made his fortune selling oval balls not only around England but also to Australasia, and the Gilbert name is still a major manufacturer of rugby products today.

n 1863, a writer in The Field asked “was the oval ball an accident from want of skill in the worker in leather in Rugby, who like the tailors then persuaded his victims that it was the true artistic shape?” The origin of rugby’s ‘outgrown egg’ is uncertain, for although it is said to have been the creation of a local shoemaker named Richard Lindon in 1862, that wouldn’t explain why Thomas Hughes had written in 1857 that the ball was “pointing towards the School or island goal.” Spherical balls can’t point. But even if HJ Lindon’s son was correct in advertising himself as the son of the “inventor of the true rugby ball and also inflator for the same,” the family foolishly failed to patent the idea. Instead it was their rival and Lindon’s possible former employer, William Gilbert, who made his fortune selling oval balls not only around England but also to Australasia, and the Gilbert name is still a major manufacturer of rugby products today.

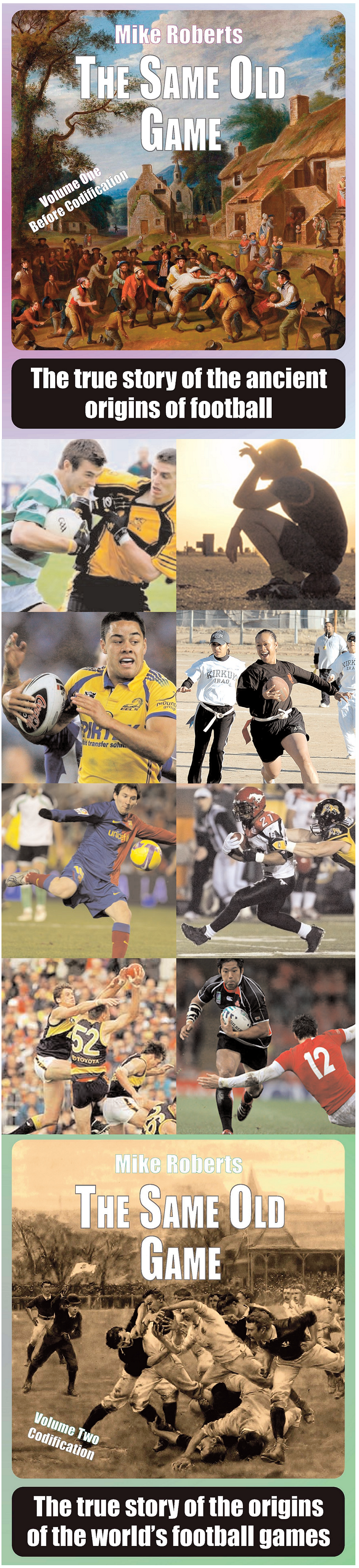

Click here to buy the book and read the whole story.

Leave a comment

Comments 0