22. Laying down the laws: The Football Association is born

Not in their wildest dreams did the founders of the FA think at the time that the proceedings of those meetings in a cigar-stained upstairs room of an inn in the London of gaslights and hansom cabs was going to have an influence on cultures from Waikato to Brazzaville.

An editorial in the Field in 1861 asked “What happens when a game of football is proposed at Christmas among a party of young men assembled from different schools? Alas! The Eton man is enamoured of his own rules, and turns up his nose at Rugby as not sufficiently aristocratic; while the Rugbeian retorts that ‘bullying’ and ‘sneaking’ are not to his taste, and he is not afraid of his shins, or of a ‘maul’ or ‘scrimmage’. On hearing this the Harrovian pricks up his ears, and though he might previously have sided with Rugby, the insinuation against the courage of those who do not allow ‘shinning’ arouses his ire, and causes him to refuse to lay with one who has offered it. Thus it is found impossible to get up a game.”

An editorial in the Field in 1861 asked “What happens when a game of football is proposed at Christmas among a party of young men assembled from different schools? Alas! The Eton man is enamoured of his own rules, and turns up his nose at Rugby as not sufficiently aristocratic; while the Rugbeian retorts that ‘bullying’ and ‘sneaking’ are not to his taste, and he is not afraid of his shins, or of a ‘maul’ or ‘scrimmage’. On hearing this the Harrovian pricks up his ears, and though he might previously have sided with Rugby, the insinuation against the courage of those who do not allow ‘shinning’ arouses his ire, and causes him to refuse to lay with one who has offered it. Thus it is found impossible to get up a game.”

It is not that football didn’t have rules. It had too many, and over the next two or three years the sports papers regularly discussed the problem not just of seeking some kind of compromise between the public schools, with John Dyer Cartwright of The Field playing a prominent role in mediating the discussion, but also creating a game that “our lusty slogging dependents of the plough or spade” would feel comfortable with too. “The savage rouge or the wild broken bully would cause a vast sensation among our agricultural friends” wrote an Etonian in 1861.

The man who really got things moving was Ebenezer Cobb Morley, captain of Barnes, who called a meeting on October 26, 1863, at the Freemason’s Tavern in Great Queen Street, London, which was attended by eleven football clubs from the area, plus a number of observers from no particular club. Although the public schools were invited, the response was poor, with only Charterhouse represented at meeting where it was noted that “it is desirable that a football association should be formed for the purpose of settling a code of rules for the regulation of the game.”

They decided to call themselves the Football Association, and Arthur Pember was named president, a peculiar choice for he had no particular history as a footballer or administrator, but as he had not attended public school he may have been considered a neutral mediator of the long discussion of “general rules as to length of pitch, width of goals, height of goals, crossbar or tape, when a goal should be won … offside, touch, behind the goal-lines, hard play, hacking, holding, mauling, packs, running with the ball, fair catch, charging, settlement of disputes, boots, throwing the ball, knocking on” and other issues.

Nothing definitive was settled that evening, and it would take five further meetings to decide on the final set of laws, with further  suggestions arriving in the form of letters from the likes of Charles Thring at Uppingham, from Sheffield FC and most importantly from Cambridge University, whose composite code particularly impressed the founder members of the FA, especially as they had been designed by representatives of different public schools, making it “appear to be the most desirable code for the association to adopt.” These rules included a strict offside law, by which no player could move ahead of the ball, and the inclusion of Eton’s ‘rouge’, whereby “when a player has kicked the ball beyond the opponents’ goal line, whoever first touches the ball when it is on the ground with his hand may have a free kick bringing the ball straight out from the goal line.” Effectively, this was exactly the same thing as the ‘try at goal’ in rugby. All of these elements would be adopted by the FA, but this was not rugby. It was a kicking game, in which “hands may only be used to stop a ball and place it on the ground before the feet.”

suggestions arriving in the form of letters from the likes of Charles Thring at Uppingham, from Sheffield FC and most importantly from Cambridge University, whose composite code particularly impressed the founder members of the FA, especially as they had been designed by representatives of different public schools, making it “appear to be the most desirable code for the association to adopt.” These rules included a strict offside law, by which no player could move ahead of the ball, and the inclusion of Eton’s ‘rouge’, whereby “when a player has kicked the ball beyond the opponents’ goal line, whoever first touches the ball when it is on the ground with his hand may have a free kick bringing the ball straight out from the goal line.” Effectively, this was exactly the same thing as the ‘try at goal’ in rugby. All of these elements would be adopted by the FA, but this was not rugby. It was a kicking game, in which “hands may only be used to stop a ball and place it on the ground before the feet.”

Only two rules sparked any major disagreement. The first was the idea that “a player shall be entitled to run with the ball towards the adversaries’ goal if he makes a fair catch or catches the ball on the first bound” and the other was that if a player did decide to run “any player on the opposite side shall be at liberty to charge, hold, trip or hack him.” None of this was permitted by the Cambridge rules, but several founder members of the FA felt that it should, and the most outspoken defender of the cause was Francis Campbell of Blackheath. By 10 votes to 9, his motion was carried.

Morley and Pember were clearly unhappy about the decision. As Morley said “if we carry those two rules, it will be seriously detrimental to the majority of clubs … Mr Campbell himself knows well that the Blackheath clubs cannot get any three clubs in London to play with them whose members are for the most part men in business, and to whom it is of importance to take care of themselves.”

Campbell retorted that “hacking is the true football game. And if you look into the Winchester records you will find that in former years men were so wounded that two of them were actually carried off the field, and they allowed two others to take their places … I say they had no business to draw up such a rule at Cambridge, and that it savours far more of the feelings of those who liked their pipes and schnapps more than the manly game of football … If you do away with it you will do away with all the pluck and courage of the game, and I will be bound to bring over a lot of Frenchmen who would beat you within a week’s practice.”

Despite the FA already having voted to include hacking and running with the ball, at a later meeting Morley and Pember managed to get the decision overturned, despite Campbell’s not entirely unjustified protestations about the dodgy democracy involved and the threat that if the resolution was carried “we shall not only feel it our duty to withdraw our names from the list of members of the association, but we shall call a meeting … with the other clubs and schools to see what they think of it.” These were the seeds of the division of the football community into soccer and rugby. But it’s curious to note that one of the main bones of contention, the deliberate kicking of opponents’ shins, would nowadays be unthinkable on a rugby field but is still commonplace in soccer!

Despite the FA already having voted to include hacking and running with the ball, at a later meeting Morley and Pember managed to get the decision overturned, despite Campbell’s not entirely unjustified protestations about the dodgy democracy involved and the threat that if the resolution was carried “we shall not only feel it our duty to withdraw our names from the list of members of the association, but we shall call a meeting … with the other clubs and schools to see what they think of it.” These were the seeds of the division of the football community into soccer and rugby. But it’s curious to note that one of the main bones of contention, the deliberate kicking of opponents’ shins, would nowadays be unthinkable on a rugby field but is still commonplace in soccer!

The FA had created soccer, although it was a very different game to the one played today. The ball could still be caught in the air to claim a free kick (as it still is Australia today). If the ball went out of bounds, the first player from either side to touch it got to put it back into play, and thrown-ins were taken underarm at right angles to the touchline as in rugby today. No forward passing was allowed, the goals had no crossbar. There were no goalkeepers, and the players changed ends after each goal, with nothing whatsoever mentioned about the length of the match, a break in play or referees, all of which were matters for the teams to decide on the day.

On December 19, 1863, the first ever game using the new FA rules was played between Barnes and Richmond and The Field reckoned that “very little difficulty was experienced on either side in playing the new rules, and the game was characterised by good temper, the rules being so simple and easy of observance that it was difficult for disputes to arise.”

On December 19, 1863, the first ever game using the new FA rules was played between Barnes and Richmond and The Field reckoned that “very little difficulty was experienced on either side in playing the new rules, and the game was characterised by good temper, the rules being so simple and easy of observance that it was difficult for disputes to arise.”

It would appear that the Football Association had been an immediate success. But that wasn’t really the case at all. Very few clubs even in London took much notice of the new rules, and seven years later, in 1868, it was even written that “a Football Association, it may be remembered, was formed some years ago … It was a praiseworthy attempt and deserved to succeed, but unquestionably it did not … it is certain the scheme fell through, having failed to obtain the necessary support.”

As it happens, the FA still existed in 1868. Despite achieving remarkably little in its first decade, it did eventually manage to get its voice heard and start attracting new members. By the 1870s, the game that had so drastically failed to impress was well on its way to becoming a national obsession, and to this day the Football Association is the senior governing body of soccer in England.

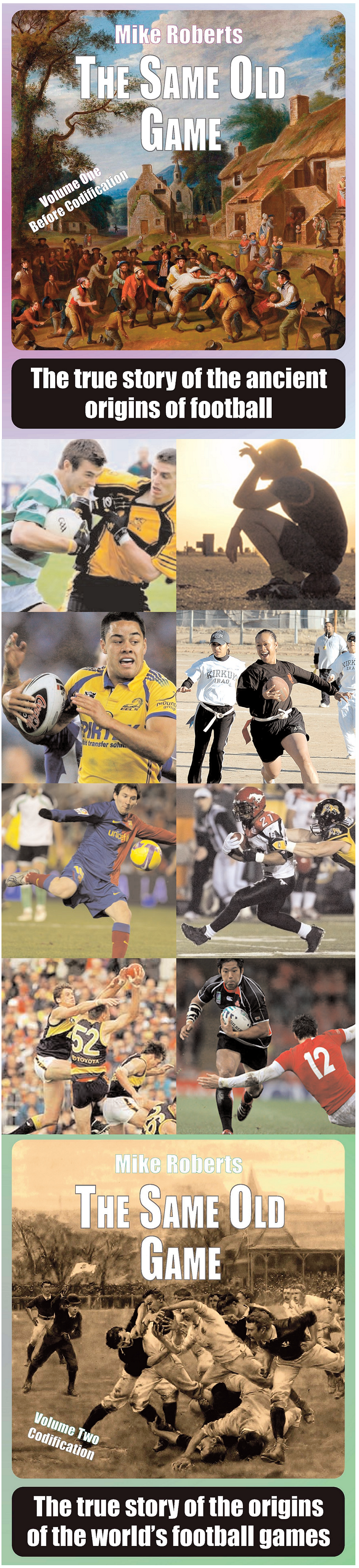

Click here to buy the book and read the whole story.

23. HISTORIC ASSOCIATIONS: How the FA’s game became the world’s game

Leave a comment

Comments 0